Egyptian temples were built for the official worship of the gods and in commemoration of the pharaohs in Ancient Egypt, and regions under Egyptian control. Temples were seen as houses for the gods or kings to whom they were dedicated. Within them, the Egyptians performed a variety of rituals, the central functions of Egyptian religion: giving offerings to the gods, reenacting their mythological interactions through festivals, and warding off the forces of chaos. These rituals were seen as necessary for the gods to continue to uphold maat, the divine order of the universe. Housing and caring for the gods were the obligations of pharaohs, who therefore dedicated prodigious resources to temple construction and maintenance. Out of necessity, pharaohs delegated most of their ritual duties to a host of priests, but most of the populace was excluded from direct participation in ceremonies and forbidden to enter a temple's most sacred areas. Nevertheless, a temple was an important religious site for all classes of Egyptians, who went there to pray, give offerings, and seek oracular guidance from the god dwelling within.

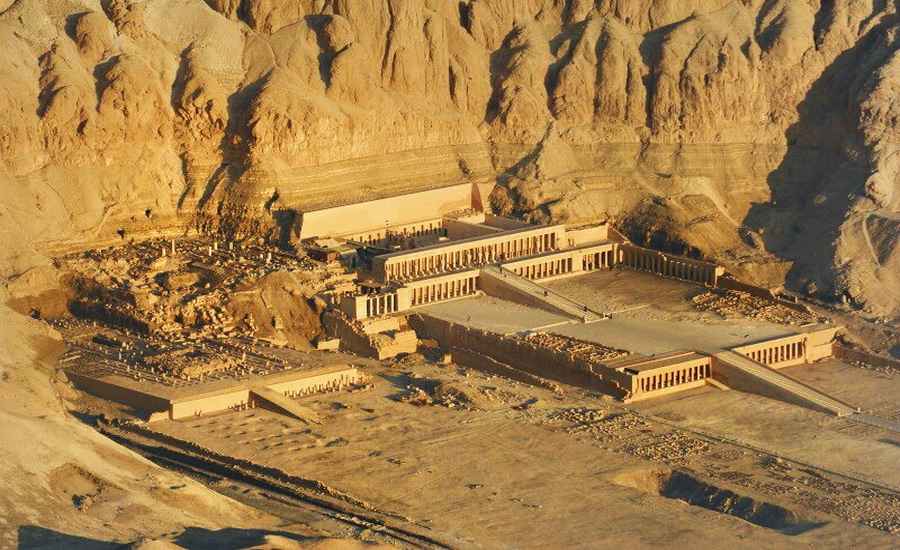

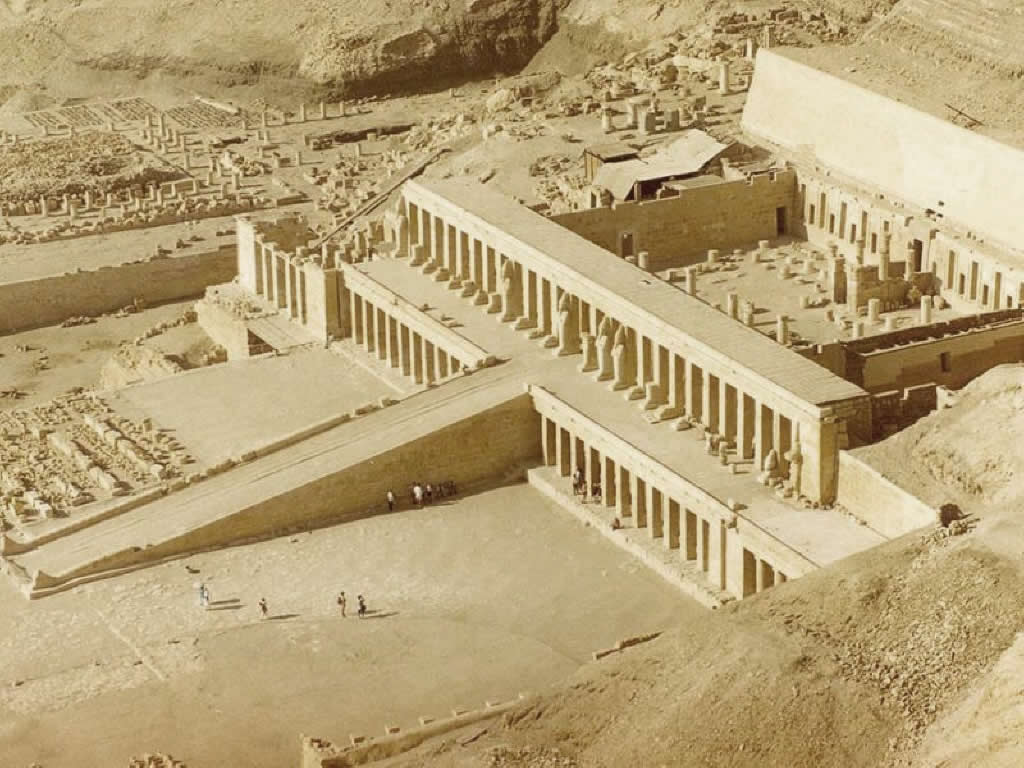

The most important part of the temple was the sanctuary, which typically contained a cult image, a statue of its god. The rooms outside the sanctuary grew larger and more elaborate over time, so that temples evolved from small shrines in the late Predynastic Period (late fourth millennium BC) to massive stone edifices in the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC) and later. These edifices are among the largest and most enduring examples of Egyptian architecture, with their elements arranged and decorated according to complex patterns of religious symbolism. Their typical design consisted of a series of enclosed halls, open courts, and massive entrance pylons aligned along the path used for festival processions. Beyond the temple proper was an outer wall enclosing a wide variety of secondary buildings.

A large temple also owned sizable tracts of land and employed thousands of laymen to supply its needs. Temples were therefore key economic as well as religious centers. The priests who managed these powerful institutions wielded considerable influence, and despite their ostensible subordination to the king they may have posed significant challenges to his authority.

Temple-building in Egypt continued despite the nation's decline and ultimate loss of independence to the Roman Empire. With the coming of Christianity, however, Egyptian religion faced increasing persecution, and the last temple was closed in AD 550. For centuries, the ancient buildings suffered destruction and neglect. But at the start of the 19th century, a wave of interest in ancient Egypt swept Europe, giving rise to the science of Egyptology and drawing increasing numbers of visitors to see the civilization's remains. Dozens of temples survive today, and some have become world-famous tourist attractions that contribute significantly to the modern Egyptian economy. Egyptologists continue to study the surviving temples and the remains of destroyed ones, as they are invaluable sources of information about ancient Egyptian society.

Design and decoration

Like all ancient Egyptian architecture, Egyptian temple designs emphasized order, symmetry, and monumentality and combined geometric shapes with stylized organic motifs. Elements of temple design also alluded to the form of the earliest Egyptian buildings. Cavetto cornices at the tops of walls, for instance, were made to imitate rows of palm fronds placed atop archaic walls, and the batter of exterior walls, while partly meant to ensure stability, was also a holdover from archaic building methods. Temple ground plans usually centered on an axis running on a slight incline from the sanctuary down to the temple entrance. In the fully developed pattern used in the New Kingdom and later, the path used for festival processions—a broad avenue punctuated with massive doors—served as this central axis. The path was intended primarily for the god's use when it traveled outside the sanctuary; on most occasions people used smaller side doors. The typical parts of a temple, such as column-filled hypostyle halls, open peristyle courts, and towering entrance pylons, were arranged along this path in a traditional but flexible order. Beyond the temple building proper, the outer walls enclosed numerous satellite buildings.

The temple pattern could vary considerably, apart from the distorting effect of additional construction. Many temples (rock temples) were cut entirely into living rock, as at Abu Simbel, or had rock-cut inner chambers with masonry courtyards and pylons, as at Wadi es-Sebua. They used much the same layout as free-standing temples but used excavated chambers rather than buildings as their inner rooms. In some temples, like the mortuary temples at Deir el-Bahari, the processional path ran up a series of terraces rather than sitting on a single level. The Ptolemaic Temple of Kom Ombo was built with two main sanctuaries, producing two parallel axes that run the length of the building. The most idiosyncratic temple style was that of the Aten temples built by Akhenaten at el-Amarna, in which the axis passed through a series of entirely open courts filled with altars.

The traditional design was a highly symbolic variety of sacred architecture. It was a greatly elaborated variant on the design of an Egyptian house, reflecting its role as the god's home. Moreover, the temple represented a piece of the divine realm on earth. The elevated, enclosed sanctuary was equated with the sacred hill where the world was created in Egyptian myth and with the burial chamber of a tomb, where the god's ba, or spirit, came to inhabit its cult image just as a human ba came to inhabit its mummy. This crucial place, the Egyptians believed, had to be insulated from the impure outside world. Therefore, as one moved toward the sanctuary the amount of outside light decreased, and restrictions on who could enter increased. Yet the temple could also represent the world itself. The processional way could therefore stand for the path of the sun traveling across the sky, and the sanctuary for the Duat where it was believed to set and to be reborn at night. The space outside the building was thus equated with the waters of chaos that lay outside the world, while the temple represented the order of the cosmos and the place where that order was continually renewed.